Looking All Ways Always

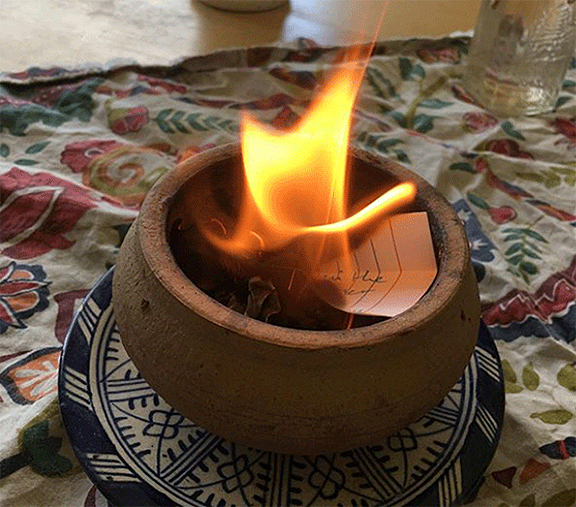

I recently found a faded, wrinkled, penciled list of hopes and dreams I’d written for what I believe was the first and only end of year Burning Bowl ceremony I’ve attended. This celebration happened in the early 1990’s, and if I remember the evening’s events correctly, our host had to stop me from tossing my future-oriented intentions into the bowl with the past’s sorrows.

A Burning Bowl ceremony involves participants writing down thoughts, feelings, or situations they wish to release or get over; these papers are set on fire in the bowl; then, the smoke from the burning paper symbolizes the process of letting go. I don’t remember what I let go of, but my hopes list includes good physical health.

While most of us don’t think of ourselves as such, we are all multi-cellular organisms whose predecessor life forms, primeval bacteria, evolved in time and space along with everything else. Our inquiring minds want to know, yet it’s pointless to try to figure out when the first human told another human that the sun was starting to get higher in the sky so it might be prudent to mark its movement for future reference. Stonehenge in England is thought to mark the movement of the sun; Stonehenge is pre-historic. Giorgio Tsoukalos of the TV series “Ancient Aliens,” suggests that it was aliens who built or designed Stonehenge and other sites around the world, but truly, who knows for sure?

What we do know is that most of the traditions baked into our western world view came from civilizations rooted around the Mediterranean. The 2021 book, “The Dawn of Everything” describes society in such a way as to challenge Western readers’ embedded cultural algorithms. Authors David Graeber and David Wengrow describe conversations between Lahontan, a French governor in Montreal and the American Kandiaronk, an Indigenous Wendat sage. Of course, the first “Americans” were those who lived here. Those Americans spoke many languages.

“The Dawn of Everything” seeks to provide “A New History of Humanity” acknowledging that there is much we cannot know for sure. Another book, Siddhartha Muhkerjee’s “The Song of the Cell” explores life on the micro-level. Each of us is a cellular ecosystem interacting and responding to other ecosystems. Our genetic inheritance passes through germline cells. Our bodily cells replace themselves regularly. Dr. Mukherjee describes cellular reality from a medical perspective, but some ancient philosophers understood the process of renewal. Philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus is said to have said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it is not the same river and he is not the same man.”

“The Song of the Cell” and other books suggest brain cells, neurons, don’t reproduce like other cells. My reading, and my experience with my own brain injury, suggest to me that while dead neuronal cells don’t grow back, neurons elsewhere in the brain might, over time, reconnect to memories and learning that became directly disconnected through brain trauma. We are in a better place to understand loss consciousness and its aftermath. Current MRI technology can reveal injuries older imaging technologies couldn’t detect.

Every night during sleep, a healthy brain in a safe place will produce enough cerebrospinal fluid to refresh brain tissue. During healthy safe sleep, the brain sorts, and stores information about the day’s events. Memory exists so we can learn, live, discern, and plan. I hope today’s behavioral and learning researchers stay mindful of Heraclitus’s words.

Probably not unlike some ancient festivals and the days that followed, New Year’s Day is often celebrated as a day for recovering from hangovers and watching football on TV. Christianity cancelled celebrations of Roman deities; still when the ancient Roman religion gave way to Christianity, seasonal Roman celebrations re-emerged as religiously Christian observances. And, today, our Julian calendar months are named for Roman gods and goddesses while some days of the week are named for Norse deities. Belief, culture, and human consciousness exist on a continuum.

January is named for the Roman god Janus. Janus is depicted as having two faces, facing backward and forward. At intersections, Janus might have four faces facing four ways; and, while some images show Janus with distinct male and female features, the two-faced male image is most common. Janus is associated with gates, passageways, beginnings, endings, and duality. Romans sought Janus’s blessings during coming-of-age celebrations, transitions, as in the New Year, and weddings. Janus looking backward and forward reminds us that there is a past and a future inherent in every given moment. There is duality, or, truly, multiplicity in every moment.

Let us choose peace, health, and wholeness in the New Year.