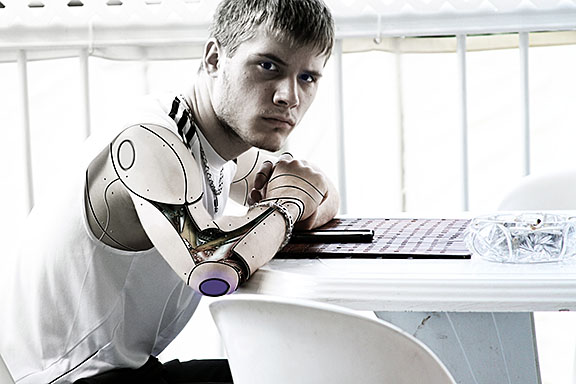

Human to Robot, Robot to Human

Perhaps you’ve seen it —the viral video of Boston Dynamics robots doing amazingly humanoid gymnastics tricks, riding skateboards, performing chores, and looking astoundingly fluid— including just a touch of very human-looking lack of balance, or misstep, that only adds to your discomfort in watching them.

Of course, it’s been predicted for a very long time that robots and AI (artificial intelligence) would one day challenge humans, and even create a bit of a moral dilemma for us as they began to “think,” as in plan, intend, react, regret.

Two things I’ve learned about recently have been as concerning and fascinating as some of the other AI innovations we’ve covered here in previ ous columns. One is the advances in that “wearable” technology you probably have that keep track of your daily steps and fitness. The other is the “grab and go” store brought to you by the people who drop packages almost daily at my doorstep because I remembered I forgot to buy toothpaste when I was shopping last – Amazon.

ous columns. One is the advances in that “wearable” technology you probably have that keep track of your daily steps and fitness. The other is the “grab and go” store brought to you by the people who drop packages almost daily at my doorstep because I remembered I forgot to buy toothpaste when I was shopping last – Amazon.

The store is of concern not only because it could possibly eliminate jobs; though more likely it will simply change them from clerks checking you out to people stocking shelves and kiosks, or moving about to answer questions. The store has perfected the disconcerting art of tracking you as you move through it. As you enter, you scan your smart phone. Payment type is identified, and you are now being tracked. As you shop, anything you pick up and keep with you is added to your tally. If you linger at a shelf, pick up but don’t take an item, that information is also noted – someday soon you can expect a discount coupon or an email offering you another option on a similar item. You breeze through your shopping experience, and when you finally exit the store, you’re billed for the items that are with you when you leave. You can shop as quickly or as leisurely as you wish, and there’s never a line to annoy you.

The other item is one I never had a particular interest in owning myself, but for which I could certain see some advantages. A friend became a real aficionado of his Fitbit, though, and I began to see them on more and more wrists. Where once our watches resided, were eventually discarded because the time was quickly available from our smart phone (Hey, Siri, what time is it?), we now sport dark faced, slim bands that track our heart rate, our step count, our time spent sleeping —our REM sleep is also tracked— our calories burned.

A recent study’s results were shared on the website IFLScience.com (you can parse the meaning). Among a group of women who wore the Fitbit, “We also found that the Fitbit was an active participant in the construction of everyday life. It had a profound impact on the women’s decision-making in terms of their diet, exercise, and how they traveled from one place to another. Almost every participant took a longer route to increase the number of steps they took (91%) and amount of weekly exercise (95%) they did. Most increased their walking speed to reach their Fitbit targets faster (56%). We also saw a change in eating habits to more healthy food, smaller portion sizes, and fewer takeaways (76%).” But there is, warned the scientists, a “darker side.” “The idea that technology is both liberating and oppressive, first articulated by philosopher Lewis Mumford in the 1930s, started to shine through. When we asked the women how they felt without their Fitbit, many reported feeling “naked” (45%) and that the activities they completed were wasted (43%). Some even felt less motivated to exercise (22%). Perhaps more alarming, many felt under pressure to reach their daily targets (79%) and that their daily routines were controlled by Fitbit (59%). Add to this that almost 30% felt that Fitbit was an enemy and made them feel guilty, and suddenly this technology doesn’t seem so perfect.”

I’ve already noted my discomfort with the idea that even if you don’t have an Alexa (or a Fitbit) listening in on your life, your phone can essentially perform the same function. But your wearable device is also capable of attending to your interests without your announcing them, your choices, times of day when you’re tired or most active – rather like a lie detector test that relies on heart rate and galvanic skin response, your wearable device could someday detect interest in a television program or commercial. It might note where you are (in a store, for example) and could (and no doubt will) eventually be able to determine if an item has caught your attention.

It’s an interesting cross-over: robots are programmed devices that are becoming daily more and more human-like in their ability to “think.” As we adopt more wired appendages, we become more and more data sets rather than individuals – more robotic. We’re warned when it’s time to leave, how much we’ve eaten, if we’ve walked enough today, and that our brother’s birthday is coming up and he’d like a gift certificate for fishing gear. No thinking required.

Try this: next time you can’t remember the name of a movie or the year Kennedy was shot, search your memory rather than looking it up on the phone. See how long before you give in to the impulse to let your device handle it.