AI Brands

A little history on brands and selling a brand.

The notion of a “brand” goes back even further than I was originally thinking – and can be traced to nearly 3000 years BC when images of branding cattle show up in Egyptian tombs. (Wikipedia)

While a name, and certainly a family name, has long constituted a “brand” of sorts, the idea of putting a specific mark on an object or animal, such as a coin or head of cattle, clearly constituted adding an ownership or authority to that thing that it lacked without it. A state assured that the specifically-marked coin was “of the realm,” and a brand on a cow’s flank indicated who claimed ownership.

Potters and other artisans, particularly in the Far East, marked their work with a signature, and eventually (yet still in the BC era), commodities were marked with the maker when quality could be assured by purchasing a particular “brand” of things like cosmetics, medicines, textiles and even alcohol.

The ancient Romans were familiar with something called a “titulus pictus,” or a picture inscription that designated what was in an amphora, for example, who made it, when, and what it was made of.

In other words, branding is hardly something new.

Of course, the idea was taken to an entirely different level once printing and newspapers were made widely available. Though hallmarks and watermarks and silver makers marks date back to Medieval and craft guild days, our more modern concept of a “brand” is clearly the product of advertising, and the battle for the attention and preference of a customer.

Especially favored were brands whose name became, literally, the name of the class of product – so, “Zipper” is actually a brand name, but now is used whenever a slide closure is referenced. Coke, to many, is simply a soft drink. Chap Stick, Band-Aid and Kleenex are other brands which have achieved category status.

The “advertising age” enabled this kind of rise to prominence – heavy, persistent advertising promoted certain brands to the extent that when people thought of a “facial tissue,” they immediately thought of “Kleenex,” and if you asked for a Kleenex, everyone else knew immediately what you wanted.

Advertisers, with print, then billboards, then radio, then television, had quick and relatively inexpensive access to enormous numbers of consumers, and used fun and compelling imagery, memorable jingles and slogans to gain and maintain “top of mind” status, so when shopping for oatmeal, the consumer was likely to immediately know and have a positive association with Quaker Oats, thanks to the name having been repeated so often.

With the Internet, the game ratcheted up not just a notch or two – but enormously.

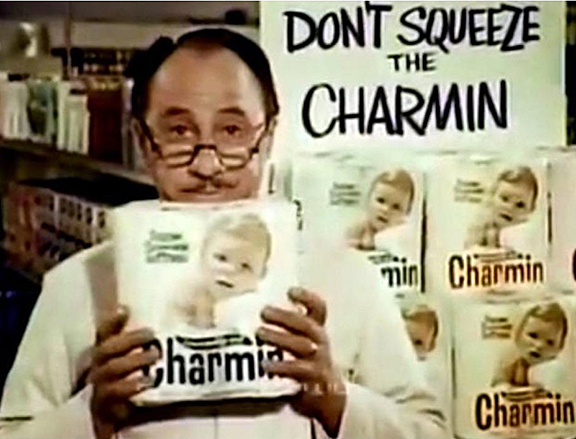

Where print and television, and radio to an extent, definitely coupled a person/personality with a product, like the famous Mr. Whipple who could not resist squeezing the Charmin,’ and Flo was sure to be offering you Progressive Insurance, a new level of advertising was achieved when Madison Avenue met “influencers.”

The Influencer is (according to website BrightEdge) “… a person who is regarded as an expert within their particular field that also has a steady following. People trust their opinions, and thus their endorsements carry a considerable amount of weight. There is a growing interest in experts who have a large social influence and presence via social media.”

Though we haven’t necessarily called them “influencers” from earliest times, human beings have always been open to the art of influencing. Without going too far back, tracts and books, newspaper articles and gossip columns have resulted in opinions, fashion choices, demand for products and preferences in everything from what to eat for dinner to when to eat it. We tend to rely on the voices of the rich, famous, erudite and elite, and to generally follow their lead.

In the most modern era, and as many as 20 or more years ago, podcasts began to carve a space for a new breed of influencer. I recall listening to a priest, Father Roderick, a Dutch gamer, sci-fi fan, and parish priest who began a remarkably famous podcast – and eventually he spun it off into a network of like-minded “content creators.”

It was a while after that when people began recording themselves on camera, simply talking about things of interest to them. The “influencer” generation. Blogging was at the same time gaining some traction, but “vlogging” had greater appeal as it could be consumed while driving or getting ready for work or at the gym, as could podcasts or the later video-added webcasts.

It was a while after that when people began recording themselves on camera, simply talking about things of interest to them. The “influencer” generation. Blogging was at the same time gaining some traction, but “vlogging” had greater appeal as it could be consumed while driving or getting ready for work or at the gym, as could podcasts or the later video-added webcasts.

With YouTube and eventually dedicated websites – and of course the ability to share enormous amounts of data rapidly and cheaply (remember when you had to dial up for an Internet connection, and beyond a certain amount of data it was going to cost you?) – enabled pod and webcasters to develop huge audiences, and YouTube obliged by “monetizing” the casts. That is, paying the content creators to share their material by offering ads with the content once a threshold number of subscribers was achieved, in a way returning to the bad old days of broadcast TV where shows (“streams”) were free but you had to endure 4-5 ads every 15 minutes or so.

Then the “influencers” began to work directly with sponsors – again, back to the old days, in which a program might be sponsored by an individual brand, the star of the show might break into the program to read an ad for the sponsor, and the name of the brand would be built right into the program.

Now remember that many of these influencers had huge numbers of “followers.” Like popular radio and TV shows, especially syndicated ones, people made it a point to tune in when their anticipated show began daily, or weekly. The Internet has the added advantage of being able to notify followers when their favorite content creators are live, and deals are cooked up with the content creators to allow people who offer them a paid subscription to interact with them live as they go into their “member blocks.”

The advent – and advancement – of platforms like TikTok and Instagram made the “popular kids” even more so by promoting them AS THE BRAND, and focusing on what they were eating, wearing, listening to, doing, laughing at. Fads have always grabbed the attention of the young, so hair, clothing, music and other trends are latched onto and become ubiquitous before being replaced by the next big thing. Many young, and even not-so-young influencers have gained unbelievable traction, and made enormous amounts of money simply by being themselves, on camera and in the ears of their devoted acolytes.

But, like many other forms of talent and expression, a new player has entered the arena, and this player has an unusual advantage. He/she is artificial.

Per Shopify, an online platform where anyone can use the tools provided by subscription to start a business, an “…AI influencer, also known as a virtual influencer (VI), is a computer-generated character designed to resemble a real person and promote products or brands on social media platforms.”

Basically, marketers figure out their target market, create a persona that will likely appeal to that market, and then program it to unbox a product, demonstrate a product, react, and engage in a variety of ways until a good formula is found, and then tirelessly change language, costume, setting and specifics to gain worldwide attention.

One of the more popular AI influencers is Lu do Magalu, a “Brazilian” AI with over seven MILLION followers, “who” promotes retailer Magazine Luiza. Lu promotes product, interacts with fans and followers, and offers tips and tricks.

AI has also been utilized by such famous brands as Nike, Mint Mobile, and BMW, to create and perfect a campaign for a specific product or the brand itself using all the data at marketers’ command to idealize a memorable campaign.

And now, evidently, the marriage of an AI influencer, an AI marketing campaign, and an AI generated “Brand” product – like art, books, programs, courses – that are designed, programmed, and produced entirely by AI.

And the big conclusion to the story: at least for the time being, people are making money selling AI branded brands!