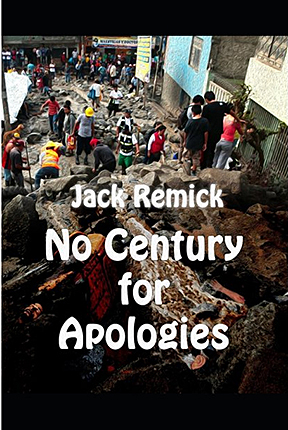

No Century for Apologies by Jack Remick

It took me a while to “hear” this book.

In fact, for the first few pages I felt a bit confused.

Let me explain: when I read, I watch a movie. This has been my habit for as long as I can remember – to the extent that when I re-read a book, even a child’s book from decades back, I see the same mental movie, complete with characters and sets – small details – that I “recognize” as I am unwinding this film in my mind. Nancy Drew’s snappy roadster (I didn’t have the slightest idea what a “roadster” was, but I imagined a detailed vehicle for Nancy and her friends); the spacious rooms at Tara in “Gone With the Wind;” the slanting angelic creatures in C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy.

Let me explain: when I read, I watch a movie. This has been my habit for as long as I can remember – to the extent that when I re-read a book, even a child’s book from decades back, I see the same mental movie, complete with characters and sets – small details – that I “recognize” as I am unwinding this film in my mind. Nancy Drew’s snappy roadster (I didn’t have the slightest idea what a “roadster” was, but I imagined a detailed vehicle for Nancy and her friends); the spacious rooms at Tara in “Gone With the Wind;” the slanting angelic creatures in C.S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy.

And yes, I could “see” the small Castle who is the center of this novel – he hides behind his diminutive stature, dark skin, and rich interior life – not to mention seven languages. I had a harder time with the places, as he travels deeper and deeper into places I had never been, the names of which I could not hear, as they were in languages I did not know. He is headed deep into the mountains of South America, encountering a shifting cast of characters whose mere descriptions I had difficulty parsing – was the woman who demanded Castle’s “favors” truly “white” haired? Did Rodriguez really drool when he drank? Did Onorato look as kindly as I imagined?

And why did the punctuation change from quotes to dashes for conversations – just paragraphs apart?

It was puzzling that last one out that finally made me “hear” the book. When the punctuation changed to the dashes, it was because the conversation was in a different tongue. The English (and perhaps other more common languages) was written with the expected quotes, and when the language shifted, a dash marked its entry. And the book began to sing to me.

It’s a troubling story, to be sure. The villains outnumber the good guys, and some of the scenes of Castle’s imprisonment, and the intrigues and betrayals make for a richly angsty tale.

But once I had discovered what was, at least for this reader, the key to the experience, I began to, through the experience of “hearing” the voices – harsh, soft, trembling, screaming, demanding – and now I could also see, however dimly and uncertainly, the muddy mountain roads, the lush apartments of the rich, the poor hovels of the impoverished, the church, the padre’s robes and the simple markets.

Remick takes us to places we’ve likely never been, and introduces us to a snarling tangle of characters who, other than Castle, and eventually Onorato, we can’t trust – they not only speak in languages we’ve likely never heard, but talk about things most of us know little of. They sing songs of enmity that go back to the ancient native people and the thoughtless intruders who invade and conquer, and still peace hasn’t come.

Just one simple scene was enough to halt me, make me “listen” and look: a woman is cooking for a man who lacks most of his teeth. She is in a shack, hunkered down near a fire, and grabbing what she calls qoy, and Castle refers to as guinea pigs, that run around loose about the dirt-floored hut. The description of her simply grabbing a few, quickly and artfully popping them from their skins, boning them and tossing them into her simmering pot with potatoes was both a jangling song and a dark visual.

But for once in my reading life, I could “hear” the flames popping, and the water bubbling.

This is an artful book; short, compelling, and powerful. And after I had finished, I turned the book over to read the description: “The screech of boulders pulverized…the town became silent…the silence jarring. Then, out of the consuming darkness that lends its primordial touch of fear to chaos, came the first wailings of death.”

And I realized that maybe I’d caught the sound of the book.