Science: The Last Word?

I was contemplating “science.” What it is, what it isn’t, and how heated the arguments have grown over what and who gets to call the strikes and hits when it comes to “science.” Of course, this is far from new.If we think we have answered that question, and that Science Has the Last Word, consider some of the more famous disputes over who owned science:

Pope Urban VIII versus Galileo: though it seems to us now that Galileo was unjustly persecuted by the Church over his heliocentrism, the actual scientific “proof” that the Earth revolves around the sun was lacking in Galileo’s time, and needed the direct evidence that Newtonian mechanics would supply, and the 18th century’s observation of light.

Or Voltaire vs. Needham: Where does the embryo come from? Is it conceived by parents (Needham), or can it be generated spontaneously (Voltaire) by an act of God? Now we’re arguing about when an embryo becomes a human life – and one day, perhaps, science will deem our arguments on this score as fundamentally flawed as were Voltaire’s.

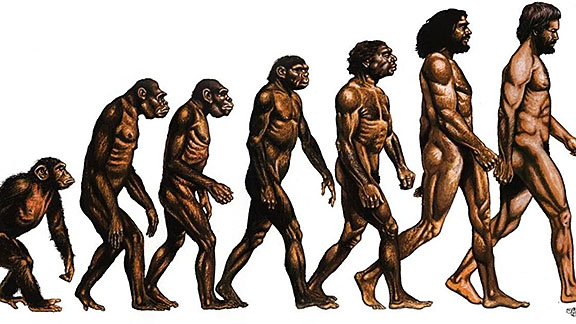

The Wilberforce-Huxley debate followed the publication of Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species,” and centered on an exchange in which Wilberforce (a creationist) is said to have asked Huxley (a Darwinist) whether it was through his grandfather or his grandmother that he claimed his descent from a monkey. While there are still “missing links” in Darwinism, science has rallied to the idea that evolution, and natural selection, are “scientific.”

In the 19th century, science was trying to determine the age of the Earth, and, lacking the radiometric dating that arrived in the mid-20th century, famously got it wrong. Lord Kelvin, the renowned physicist of that era, argued for 100 million, later reduced to 20 million years – though today’s best estimate is about 4.5 billion, based on modern technology. Of course, having been wrong before, it’s probably best to say “today’s best estimate, given what we now know and can measure…” in all cases attempting to date the universe!

And poor Alfred Wegener. Though he wasn’t the first to postulate that Earth’s landmass was once one huge continent and that sections of it eventually moved apart, he had some of the details wrong, such as the speed of the “continental drift” that pushed the various continents apart, he also, some speculate because he was not a formally trained geologist, lacked a theory for the “how” of this drift: what was the mechanism, the force, that pushed the plates apart? Though most scientists now agree that the Pangea theory is correct, there are still investigations being conducted into how Pangea ended up in our current continental configuration.

And in the mid-20th century, we saw John Derek Freeman, a New Zealand anthropologist, criticize Margaret Mead and her seminal work, “Coming of Age in Samoa.” Is it nature (Freeman’s position) or nurture (Mead) that dictates human behavior? Mead was convinced by her time spent with the relatively free Samoan people that particularly adolescent difficulties were not bred but taught, whereas Freeman argued that human behavior has more to do with the equipment of the human being. And perhaps this is another argument that will bubble to the surface as youthful behavior and choices become ever more challenging to adults from other generations to understand. Is it something in the food supply, or just kids being kids?