Spirit Technology

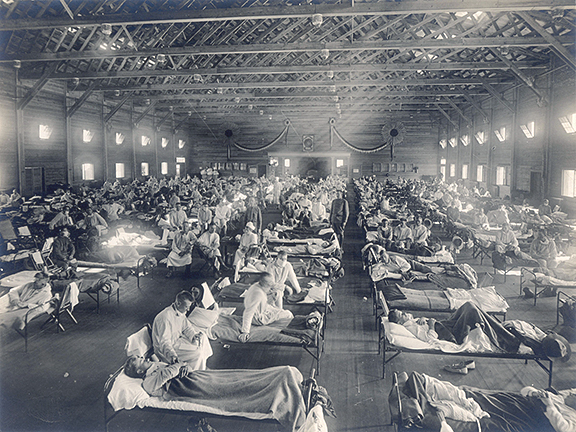

I’ve spent a bit of time reading about pandemics and plagues, either as research or because it seems like the main topic of interest for most these days. Along with a lot of interesting, if slightly depressing, details about the 1918 pandemic, I’ve read about the major outbreaks of bubonic plague, the Broad Street cholera epidemic in the UK in the 1854, “Typhoid” Mary Mallon, and others.

Richard Bergh: Hypnotisk seans.

NM 1851

But just when you think you’ve learned all there is to know, I discovered something unexpected in the world of science and history – and in some cases, spurious “technology.”

In this case, the story is about the sudden resurgence of interest in communicating with the dead – spiritualism – that occurred as a result of the 1918 pandemic. Each time a mysterious illness suddenly appears, and devastates the world we know, people respond with emotional and spiritual crises. Needless to say, the pandemic – the Spanish influenza – was terrifying given its death toll (it eventually killed about 50 million total), and coupled with that, the world was just at the closing moments of its first “world” war. The interest in what lay “beyond” heated up. Contributing to that were such notable names such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who became believers. Many assume he was grasping for hope because of his son’s and brother’s deaths, likely of the flu. This is a good point at which to note – Spiritualism remains for some, as it was for Doyle, a religious or spiritual path, but for purposes of this article, we’ll be sticking with the mechanical means by which some conjured their “spirits.”

Spiritualism, though not known by the name at the time, was to an extent, the stepchild of the interests and “technologies” of two far older players: Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) and Franz Mesmer (1734-1815). Swedenborg was an inventor, scientist, and philosopher who espoused a hierarchical setup for heaven and hell – and warned people not to seek spirits as you couldn’t be exactly sure where they were “living.” Mesmer, on the other hand, investigated and popularized “mesmerism,” or hypnotism, inducing trances in willing subjects, and through them, sometimes talking with disincarnate spirits.

In the early to mid-1800s, Spiritualism caught on in Upstate and Western New York, with, notably, the Fox Sisters, who used a variety of stage magic tricks, evidently, to confer with the beyond. Other spiritualists joined them in putting on shows, and eventually such shows became regular entertainment staples. Among the many technical devices employed by magician/spiritualists were: slate writing (a piece of chalk is held between two slates, and the medium is induced to write for the spirit); table-turning (a table is tilted toward a letter or answer on its top, by such means as a hook worn on the medium’s wrist, which, in the dark of the séance room, fits neatly under the rim of the table); or spirit photography (essentially double-exposure, or other photographic tricks – though given the popularity of Photoshop, everyone seems to be onto this one).

By 1879, the famous Lily Dale was incorporated as the Cassadaga Lake Free Association, where practitioners would go and meet and display their skills, and enjoy the beauty of the lake and countryside, and still do to this day.

By the early 20th century, spiritualism as a craze had died down, though not disappeared, but with its resurgence post-war, it had returned full-force, and became the study and cause of such debunkers as master magician Harry Houdini, who, incensed by those who would use the grief of the survivors (like his good friend Doyle), made outing scam spiritualists his cause. Challenged by Scientific American, Houdini took on the renowned medium Mina (“Margery”) Crandon, and though he could explain all her methods, she seemed to get the better of him when she cursed him, and he died, of septic shock, as she “predicted.” Around the same time, Ouija Boards, though they’d been a parlor game since the 1890s, had a sudden resurgence in popularity as families of influenza victims and the war dead eagerly tried to contact their dead.

The end of the influenza-inspired desire to contact the spirits finally gave way to the more serious business of a new war, and by mid-century, Ouija Boards and table-tipping had fallen out of interest, though the interest in what lies beyond – and the actual means to understand it – never does.