Time and Again by Jack Finney, published: 1970

As a rule, I don’t like to review a book until I’ve finished it. It seems like cheating, somehow, and more to the point – how will I know I like the way it ends? Ok, I cheated. I read the last page already, which is something I started doing as a kid, and I have no idea why.

What I will say is, though in one way it would seem likely to ruin any suspense the book might generate – after all, I know if Joe lives ‘til the end, don’t I? But then, in another way, it allows me to evaluate the book: did the author do a good job of leading to the conclusion, or was it just tacked on? Or even better, did I forget all about that last page “cheat” because I got so involved in the story that I didn’t think about it?

What I will say is, though in one way it would seem likely to ruin any suspense the book might generate – after all, I know if Joe lives ‘til the end, don’t I? But then, in another way, it allows me to evaluate the book: did the author do a good job of leading to the conclusion, or was it just tacked on? Or even better, did I forget all about that last page “cheat” because I got so involved in the story that I didn’t think about it?

With this book, either way would have been fine, cheat or no. I’m actually surprised that in all my reading, especially of fantasy, Sci-Fi and time travel, I never stumbled on this one before. And “stumble” is about the exact way I encountered it – and I still don’t know how it ended up on my bookshelf! It was late one night, and I couldn’t sleep. I was reading some non-fiction, and my brain wasn’t quite up to that. I stumbled to the bookshelf in my room and grabbed the first thing that didn’t look too long and that I hadn’t read recently. In fact, I realized as I studied the cover, while the title looked familiar, I didn’t remember ever reading it – and it was fresh and the spine uncracked. How did it come to be there?

I settled in and couldn’t stop for several chapters (and woke up with the book in my hands).

For many readers, this is the grand-daddy of time travel books. I would guess that that’s because (and this is also one of its chief criticisms by some readers) there is no technology involved in the time travel. No machine, no special equipment or room or even stones or stellar alignment. Instead, the traveler must be in a location that existed at the time he intends to travel to, and then immerse himself in the period and place. Then, using a form of self-hypnosis, convince himself that he will, in fact, move through time (and with luck, back again to his present if he chooses). If this sounds like the film, Somewhere in Time, it does in fact use a strikingly similar technique, though since Finney wrote his book prior to the one the film is based on (in 1970), he might be given credit for the method. But as it turns out, the writer of that book (Richard Matheson, another favorite author, who wrote I Am Legend among others) based his book, published in 1975, on the writing of J.B. Priestly, who published his time travel tome in 1964. So, as of right now, it’s Priestly for the win.

Having not read either Matheson’s or Priestly’s work, I can only say that the distinguishing feature of Time and Again is the details – and our shared experience of them with the protagonist, Simon (Si) Morley. Recruited to be part of a top secret government experiment, our hero (an advertising sketch artist) becomes even more intrigued by his mission when his girlfriend shares with him a letter that confesses to a crime that leads to the suicide of the writer. They want to learn who is he, and what the “world burning” event he writes about might be.

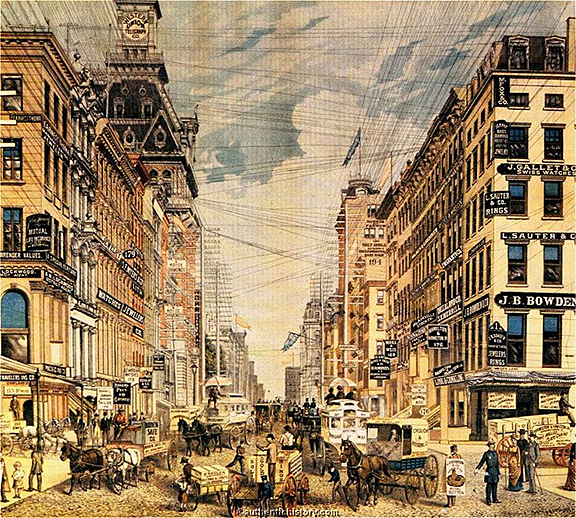

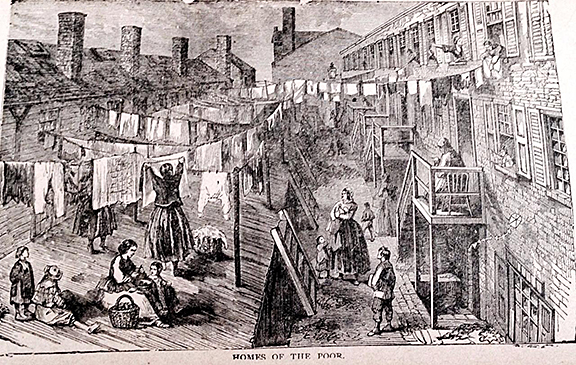

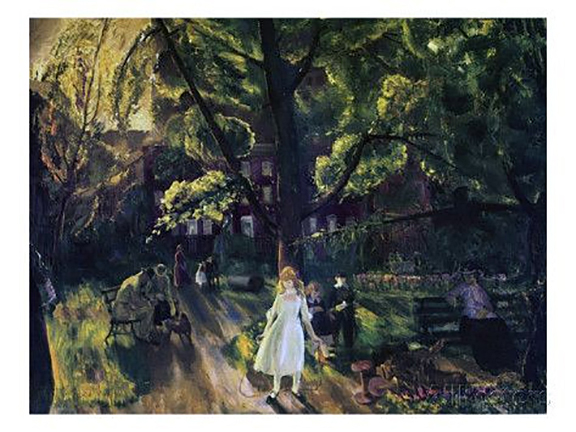

As Si travels back in time to 1882, New York City, he not only involves himself in a mystery and with some intriguing characters, but he explores the city as it was then from his home base in a then-vacant apartment in The Dakota (yes, that Dakota, the alter-ego of the Bramford of Rosemary and her baby; the home of John Lennon outside which he was killed) and we see New York City through his wondering eyes. In one long day, he arrives to find his house-mates at 19 Gramercy heading out for some sleigh-riding in the park. We are immersed in the 19th century. We can hear the bells, the clip-clop of the horses hoofs, the calls of children sledding and throwing snowballs; we can feel the chill of the day and the scratch of woolen mufflers around our necks and fur hats sitting firmly snugged on our heads; we can take part in the singing, eating, and drinking to warm ourselves later. And then we can come crashing back to our own perspective as we ride along on a bobtail trolley, in which the driver explains that he must stand outside in the freezing cold to drive the horse as a driver one night fell asleep and died of the cold as he was sitting at his post. We hear about the orphans and working children nestling down in hale bales by the river to try to stay warm; we see the pitiful attempts of the poor to wrap enough layers of clothing around themselves to try not to freeze, and the 14 hour long days of street vendors selling gadgets and fruits from baskets and bags they carry, walking and walking through the less lovely parts of town.

Suffice to say, Si gets more involved than he intends; he is threatened with the plug being pulled on the project as parallel studies have resulted in dangerous accidents and even a death; and he realizes he can’t just leave what he has discovered without trying to make it right. On that level, the story is a solidly good novel of intrigue.

But for me, it was the wonder of seeing New York not just as it was in all those old black and white photos, or advertising sketches from antique newspapers and cards that kept me enthralled, but through the eyes of someone like myself had they actually woken up there.

Peter Jackson created an absolute masterpiece of a film, They Shall Not Grow Old, about World War I, by piecing together old film clips from the era, colorizing them, adjusting the speed, and adding sound. He managed to tell a little “story” about characters – real people – young men who went to war with great good spirits and high-minded intentions, and the horror they found as the shells began to explode, the bullets to fly and their friends drop around them. It makes a period we think of only in a five-times-removed, colorless, soundless, motionless way, come alive. And suddenly the people are real; the events are real; the story is real.

If you have spent any time in New York City, you’ll recognize the landmarks Finney refers to: Broadway, 5th Avenue, The Dakota, Gramercy Park, Central Park. You’ll “see” them as you have seen them yourself. And you’ll see them as Si does when he lands in the past century, and walks around a town the tallest building of which was Trinity Church. In color. Moving, talking, shouting, real.

I do recall getting a small hint of Si’s experience when walking around Wall Street, on some of the still-cobbled side streets, and seeing the old buildings that still stand there, and being greeted by street vendors selling toys and foods and postcards. But between the author’s absolute attention to detail, and his use of old photos, new sketches, and probably staged new photos to invoke the work of 1882 – and his artist’s eye as well as his amazed time traveler’s shocks in experiencing it, we are taken along with him on an excursion that, though it was written nearly 55 years ago, reads as real to us now as it might have had we read it when it was written. Or had we actually lived it.

Finney was, himself, a advertising artist, born in 1911, and might have seen remnants of the world he takes us back to. He’s probably best known as the author of the book, The Body Snatchers, that you never read but no doubt saw the movie based upon it, The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Finney was also a prolific short story writer in the great last age of the short story, writing for Colliers, Cosmopolitan, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, McCall’s, The Saturday Evening Post, and more.

The question I’m left with, though, is this: how did that book come to be on my bookshelf, just when I was looking for a book just like it to read? Why didn’t I notice it before? Was it left there for me, perhaps?

And: what happens in the end? Questions to be answered.