Turn Up the Volume

The Volume. I’ll do my best with this subject – but it’s quite new, I’ve never worked with it, and having done a little film acting my best guess is you’d come out of The Volume more than a bit disoriented.

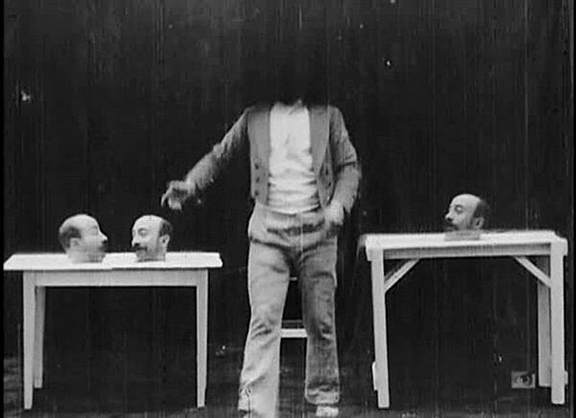

Green screen has been the gold standard for compositing a background with action in a film for several decades. In fact, compositing goes back further than that – all the way to 1898 (yes, 18). George Méliès wanted to depict a man removing his head for a film – so he basically layered multiple frames in multiple exposures to create the trick shot. The technique was repeated, improved upon, and was known as matte techniques, and could be used to add or remove something from a shot, usually one in which actors were say, standing in front of a moving background scene, or the director wanted a special effect that couldn’t be obtained with a straight shot.

In the 1930s, the “green screen” (only it was blue at the time, and known as chroma key) technique debuted. An evenly lit background of deep blue was behind (and often beneath) the actors in a scene, and then blue would then be removed from the shot, and replaced with whatever scene, moving or static, the filmmakers wanted. By the late 80s, animation was combined with live action via green screen, opening a whole new door to, especially, movies that involved fantasy or sci-fi. The development of this technique from the 30s through to recent film history went through dozens of iterations and techniques, each one focused on making the composite shot better and more believable, and solving a particular problem for that film. So, how things were lit, which colors were subtracted, how many layers were required to get a final shot, all depended on what the filmmakers were hoping to achieve – as well as who the actors were (skin tone mattered a great deal) and how they were to be costumed.

The state of the art now still involves actors and cameras – but, in a way, harks back to an old theater technique called the rear screen projection. In this technique, actors were moving around on a stage, with set pieces (chairs, tables, rocks, trees) and behind them was projected a larger environment, onto a translucent screen, from behind. You’ll see this employed in shots like the famous “driving the car” scene in which an actor or actors are supposedly in a car, and behind them is a film of the street as they pass by. It worked – sort of.

But with the “volume,” a giant wrap-around LED screen, the actors step into a large space, properly accoutered with appropriate smaller set pieces, and all around them, in a close to 360 degree arc, is a scene that looks and feels so real actors can actually “get lost” in a scene.

Volume technology doesn’t have to be huge. It can, in fact, be whatever size is required to suit the shots and the project, and can create whatever size “world” is needed – from a vast, star-swept sky of a distant planet, to an imaginary bugs-eye-view of grass and a menacing foot or hoof.

One of the more brilliant innovations of volume shooting in Stagecraft (a particular LED set used in filming for The Mandalorian and some Star Wars films) “and other, smaller LED walls (the more general term for these backgrounds) is not only that the image shown is generated live in photorealistic 3D by powerful GPUs, but that 3D scene is directly affected by the movements and settings of the camera. If the camera moves to the right, the image alters just as the real scene would and other, smaller LED walls (the more general term for these backgrounds) is not only that the image shown is generated live in photorealistic 3D by powerful GPUs, but that 3D scene is directly affected by the movements and settings of the camera. If the camera moves to the right, the image alters just as if it were a real scene.” (TechCrunch.com)

Another benefit of such shooting is that the whole cast and crew doesn’t need to be on location, either for principal shooting or re-shoots. Cinematographers travel to an exotic location and pick up a variety of shots, and if necessary, can return to layer a new background into the finished product if the script changes a bit.

If you’d like to see the technology in action: https://youtu.be/gUnxzVOs3rk

Next time I’m watching a scene from a film set in, say, 1880 in the deserts of the southwest and someone says, “How did they shoot that?” I think I’ll have a smart-alec answer.