Women in the Struggle for American’s Independence by Carol Berkin

The Onondaga Historical Association, OHA, does more than house great archives, tailor well thought-out exhibits and sell a variety of Onondaga County and Syracuse related items in a fascinating gift shop.  The organization also provides area schools, historic groups, social organizations and others with performances presenting a “first person” account from some of our storied ancestors. Among these performances are the yearly “Ghost Walks,” that take place in Oakwood Cemetery, as well as select locations around the county.

The organization also provides area schools, historic groups, social organizations and others with performances presenting a “first person” account from some of our storied ancestors. Among these performances are the yearly “Ghost Walks,” that take place in Oakwood Cemetery, as well as select locations around the county.

I’m happy to say I’ve been part of many a “walk,” as a guide or a Ghost, and one of these Ghosts is the spirit of Hannah Danforth, among, if not the first woman of European descent to live in Onondaga. She’s a delight to play, and to imagine – coming from a well-to-do background and following her husband to the “wilds of Onondaga” back some years after the American Revolution, with nothing but “bark walls and a hemlock branch roof” for shelter when they first settled here.

Recently, I was given a copy of the book, Revolutionary Women, from which some of Hannah’s story is no doubt gleaned. Because, Hannah, at least in our imagining of her, is proud of the role women played in the Revolution, and has written up brief stories of some of the more prominent ladies who did their part for “The Cause.”

Needless to say, Berkin goes into a great deal more detail about some of these women, the famous, infamous, and nameless ones, many of whom endured trials hard to fathom – and about whom we rarely think when we think “American Revolution.”

Many of us may have heard of “Molly Pitcher” in grade school, though few of us would have known that there really was, according to Berkin, no single “Molly.” It was a term applied to women who ran water to the men manning the canons, so that they could cool them as they were firing them so they didn’t overheat and fail. (That’s something that, to be honest, I’d never considered as a possibility!) There was a woman who was famous, or perhaps infamous, for taking her husband’s place at the canon, when a canon ball aimed at the Revolutionaries flew between her legs – ripping her petticoats!

While there were women whose lives of gentility were only interrupted insofar as there were few men during the months of fighting for whom to plan dances and dinners (the fighting was, at least in part, more limited during the winter months, and the officers were more free to engage in their social activities in the larger cities), there were many women who had to step up and perform the duties they normally did – cooking, cleaning, sewing, laundry, childcare, and tending gardens and managing the home – but had to undertake those of their husbands, whether managing a farm or a business. One telling paragraph cites a diary entry from a housewife, Mary Holyoke, wife of a country doctor, who entered her workweek: “Washed. Ironed. Scoured pewter. Scoured rooms. Scoured furniture Brasses and put up the chintz bed and hung pictures. (I’m starting to feel tired…) Sowed sweet marjoram. Sowed pease. Sowed cauliflower. Sowed 6 week beans. Pulled radishes. Set out turnips. Cut 36 asparagus. (Now I’m really weary…) Killed the pig, weight 164 pounds. Made bread. Put beef in pickle. Salted Pork, but bacon in pickle. Made the doctor 6 cravats marked H…” She ends her entry (which goes on) “did other things.”

Aside from managing without the protection and labor of their husbands, many of the women Berkin notes in her book were instrumental in bringing about the war. As with the men, women were loyalists, rebels, or just wished to be left alone – but many felt the pain of the taxes, and did their part to rebel by refusing to drink tea (though it was a much beloved beverage) and refusing to wear British made fabrics. Homespun became the rage among the rebellious females, who not only had to help harvest the raw materials (like cotton), but had to spin, weave, cut and stitch the clothing for themselves, their husbands, and children. And perhaps dye and embroider the garments, as well.

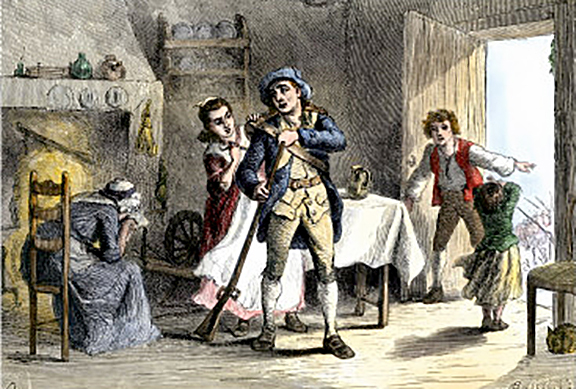

Berkin dispels at least some of the ideas I’d always had of “camp followers.” These women might very well have been the “bitchyfox jades, jills, haggs, strums, (and) prostitutes” written about by a colonel who patrolled the “Holy Ground,” a notorious meeting place near St. Paul’s Church in New York City, where the strumpets plied their trade, but a good many more of them were wives, daughters, and sisters of the fighting men, or perhaps simply women who had no other choice but to follow the army and work for pay: washing and mending clothing, cleaning bedding, cooking, fetching wood and water, nursing wounded or ill men, and then packing up all of their belonging, and often their children, and carrying the whole in baskets on their backs.

Berkin also reminds us the great risk to women from not just the enemy, but from soldiers far from home and perhaps a bit worse for a pint or two. “Ravishment” and rape were not uncommon, and the constant fear that one’s husband would be on the list of those lost, or that there would simply be nothing to feed one’s child, were constant pressures on those who remained at home, while “Johnny” went for a soldier.

There is so much more in the book – but I leave it to you to discover it. But the next time I watch a movie about the Revolution, one thing is certain: I won’t just be wondering how it might have felt to be “Johnny.” I’ll be certain to be thinking of “Jill,” as well.