Cope or Create

Difficult times result in two impulses: coping, and coming up with something new.

The first impulse is an inward path and can be seen in how we have adapted our lives to the reality of a dangerous virus. Masks, distance, limiting socialization, hand washing stations, and at-home schooling are all methods we now use to manage an unseen enemy by mainly limiting our options to minimize our exposure.

The second impulse is an extension of the story we covered in this column last month: what to do about at-odds online conversations and the platforms that support them? Cope, as in, limit your online communications, or create: come up with something (sort of) new.

Thirty years ago, our means of public discourse did not, of course, include social media. Though technically launched in about 1997 with something called SixDegrees, the 2003 advent of MySpace was probably the first most of us were aware that there was a way of presenting oneself to the world, and “making friends” with unknown others, who ideally shared your interests and ideas. Initially, before the “social media” label had been invented, MySpace was a place where bands and performers could create a profile page and let fans and followers know what they were doing, where they would be playing, and when an album or movie would be available. This early history doesn’t do justice to the “geek spaces” known as BBS’s, or bulletin boards, where subscribers would send real-time chats about games, programming, technology, and other esoterica favored by the particular board. But while popular, they never achieved the status of the social media that we have come to know and loathe/love. MySpace, with its quick adoption by high schoolers and its permissive environment in which nudity and provocative posts were rampant, sealed its fate as a generally desirable place to be showcased – and it has since adjusted its profile as a place for up-and-coming talents in the performing and visual arts.

In 2004 the game-changer that is Facebook was introduced. In one of the more brilliantly played launches, “The Facebook” (as it was known then) was available only to Harvard students that year. Believe it or not, LinkedIn also was introduced that year, though its adoption has been much slower and more targeted. Facebook continued to brand itself as “exclusive” by adding only other Ivy college students, then a select number of additional schools, then graduates of those schools, age groups, and finally was available to everyone. By limiting who could and could not play in the Facebook sandbox, it offered a whiff of snobbery that made it more desirable than it might have seemed at first.

But obviously, the real benefit to Facebook was connecting with friends and family that you might not otherwise have tracked down or had the time to contact. Photos and events could be easily shared, and above all, while not really acknowledged openly, it was a way to create your alter-ego. Your photo portrayed you as always young, fit, and desirable; your activities were the most fun, your food the most delicious, your observations the most clever and inspired.

In 2005 YouTube opened a “tv channel” for anyone to share stories. I still recall getting messages from friends and co-workers with a link to a funny or inspiring YouTube video. Remember “Candy Mountain” with Charlie the unicorn? So do I. I still laugh. Aside from funny videos and clips, you would share baby’s first words, a wedding, a beautiful sunset or snowstorm, or a clever animals video.

Can you believe Twitter has been around for 15 years? Initially limited to 140 characters (based on the 160 character limit of an SMS text message), Twitter was kind of fun in its early days. It was chatty and often silly, pithy, and clever. Now 280 characters, users overcome that problem of limited words with Twitterisms and a simple directory of 1/3, 2/3, 3/3 for longer messages, and the pattern of “tweeting” is hardly benign anymore.

Two young women shopping at the mall taking a “selfie” or self portrait with their cell phone

In 2010 Instagram launched as a visual imagery sharing platform, but like MySpace before it, quickly became driven by younger – and often raunchier – users. TikTok, again away for very clever creators to make fun, sometimes fantastic short videos, has also been somewhat limited in its universal adoption by the nature of many of the TikToks people feel compelled to make, focusing as they do on body parts and Instagram “models.”

The recent, definitely disturbing development in many social media platforms is their exploitation by people, organizations, and movements that aim to use their reach to influence opinions, spread gossip and if not falsehoods then at least dramatizations of events, and restrict their use by those they feel don’t portray the “correct” ideas and attitudes. Last month, we dealt with the evolution of social media platforms as a hybrid information distribution system and the difficulty of knowing how to legally manage such a hybrid with the laws as currently written. Now we’ll take a look at how entrepreneurs are aiming at offering users an alternative.

What has happened is, in a way, the good old DIY response to a platform trying to sort out its own best interests and those of its users: don’t like what we’re saying or how we’re saying it? Fine, we’ll create another platform that permits “the conversation” to be conducted on our terms. This would seem to be classic “American” ingenuity at its finest – simply work around the problem.

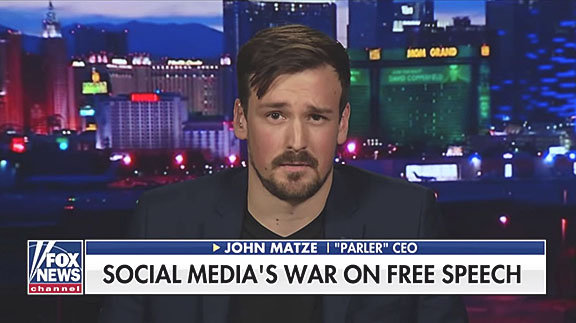

And thus there was Parler.

Parler is just one of a myriad of upstart social platforms that aim to open online speech to those Facebook or Twitter seek to silence, for good or ill. I started getting my first chat invitations to services like Signal, WeChat and WhatsApp, ostensibly for the enhanced security they offered above Facebook’s Messenger, and the generic Messenger text app, but probably in reality also to offer anonymity to users who wanted to communicate via apps and social media but feared their opinions or messages would create difficulties for them. Not too long into the “social media wars,” Parler was no longer available as an app for iPhone or Android. Other social media start-ups like Gab and Rumble took aim at Twitter and YouTube respectively, but when you look at the numbers, it’s clear that ramping up to become any kind of competition to these giants is a Herculean task. Facebook has 2.23 billion (yes, billion) MAUs (monthly active users). 65 million businesses use Facebook, and 6 million of them advertise. YouTube is in second place with 1.9 billion MAUs, and believe it or not, WhatsApp, a combo text, sharing, and centralized messaging application, owned by Facebook, is in third place with 1.5 billion MAUs. By way of comparison, Twitter comes in 12th. Needless to say, these numbers are changing all the time, and were current as of early 2020 – new stats are being published every month.

Worldwide, the Chinese are the most frequent users of social media across all forms, from messaging and VoIP to social sharing apps like TikTok. But with the influence, they now have to engage users, and influence behavior and attitudes, who uses what and how they promote and limit conversations, will continue to be important to more than just marketers in both the near and likely the distant, future.

Worldwide, the Chinese are the most frequent users of social media across all forms, from messaging and VoIP to social sharing apps like TikTok. But with the influence, they now have to engage users, and influence behavior and attitudes, who uses what and how they promote and limit conversations, will continue to be important to more than just marketers in both the near and likely the distant, future.