Memoir: Chapter One

National Public Radio’s 2021 list of 369 “Books We Love” includes four memoirs. One, “Pregnant Girl,” describes Nicole Lynn Lewis’s experience as a young mother going to college. Another, Tracy Clark-Flory’s “Want Me: A Sex Writer’s Journey into the Heart of Desire,” details a woman’s/women’s search for love, sex, and power in a freer than ever culture still defined by a traditional deep-seated masculine perspective.  Larissa Pham’s “Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy” explores her experiences of young love and trauma in connection with popular culture, past and present. Memoir number 4 is Kyle Beachy’s “The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life.”

Larissa Pham’s “Pop Song: Adventures in Art and Intimacy” explores her experiences of young love and trauma in connection with popular culture, past and present. Memoir number 4 is Kyle Beachy’s “The Most Fun Thing: Dispatches from a Skateboard Life.”

Three of the four memoirs written and recommended by women, address emotional, social, and reproductive challenges girls and women face in education, work, and relationships. The single memoir written by a male and selected by a male is about a sport, although I assume that “Want Me” includes some female perspective about sex as recreational sport. I’ve not read any of these memoirs. NPR’s and major bookseller’s websites offer discussions and detailed descriptions of each book.

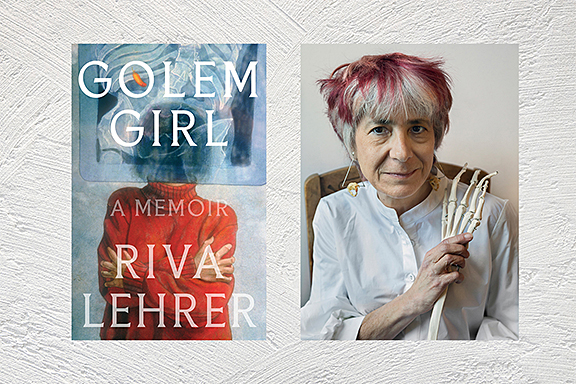

In 2021, I’ve read several memoirs. Riva Lehrer’s 2020 “Golem Girl” is Ms. Lehrer’s story of living and maturing with spina bifida. Riva Lehrer weaves tradition, culture, and scientific references into a conversational work that sent me to the dictionary more than once. Ms. Lehrer is a painter, an instructor at the Chicago Art Institute, and an instructor in medical humanities at Northwestern University. Her book includes precise harrowing accounts of her hospitalizations, reproductions of her artwork, and timely discussions of her activist work in groups united by physical injuries and challenges, but divided by gender, class, and racial perspectives. Riva Lehrer discusses labels such as “disabled” and “differently abled,” terms originating from subject and object perspectives. “Golem Girl” provides the personal perspective of one medical patient whose body is sometimes viewed as discrete parts and sometimes as a unified whole. Some of the compartmentalized parts issues involve generative physiology and all that follows.

Many physical and psychic problems originate with human beings not being allowed to precisely discuss below the waist physiology. Value judgements and “too much information” taboos facilitate confusion, not health. The body, the senses, and consciousness function as one. My memoir in progress addresses such issues.

I’ve been writing since I was in seventh and eighth grade sitting on my bed imagining idealized paper doll families with multifaceted dramatic storylines. Neo-Freudians might suggest I was seeking to unify my splintered psyche and make my unconscious conscious. I remember having little else to do. My earliest journals listed daily schedules; I was too embarrassed to write that I still played with paper dolls. My first short stories were “happily ever after” rehashes of the “West Side Story” theme.

I tried to follow my culture’s blueprints. My religion encouraged long-suffering

I tried to follow my culture’s blueprints. My religion encouraged long-suffering

do-gooding. Earlier in elementary school, I lectured playmates about language; condemning the use of racial slurs resulted in my being pointed out as having vocalized a slur in my nagging. Days or weeks later, I tried to explain myself to one of the insulted group members who responded by punching me in the face; I saw stars which I thought meant God blessed me. I still find or put myself in comparable situations, without the punching, so far. I enjoy lively discussions of diverse ideas. Still, I ask myself, have the pandemic’s ideological and social polarization, and the proliferation of denigrating cultural labels and buzzwords rendered broad-reaching interpersonal communication too risky?

I’ve not seen the new “West Side Story.” “West Side Story’s” finale song “Somewhere” always brought tears to my eyes when I played it on my piano. Playing the piano and

“Somewhere” triggers long forgotten vivid memories of grammar school.

Good? Maybe.

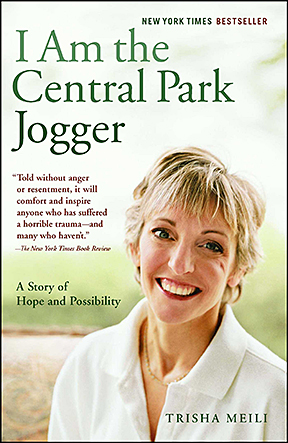

Throughout my life people have tried to get me to “snap out of it” and/or wake up to memories neural damage had separated from my consciousness. People recommended certain movies and books. My specific condition, TBI based amnesia, provided the comedic fodder for the 1987 film “Overboard,” and, the underlying theme, for Stephen King’s 1983 “The Dead Zone.” Neither fiction triggered my specific memories. A family member suggested I read Trisha Meili’s “I Am the Central Park Jogger.” I didn’t. Then

Throughout my life people have tried to get me to “snap out of it” and/or wake up to memories neural damage had separated from my consciousness. People recommended certain movies and books. My specific condition, TBI based amnesia, provided the comedic fodder for the 1987 film “Overboard,” and, the underlying theme, for Stephen King’s 1983 “The Dead Zone.” Neither fiction triggered my specific memories. A family member suggested I read Trisha Meili’s “I Am the Central Park Jogger.” I didn’t. Then

I did. I now sense common ground with Trisha Meili and Riva Lehrer. If I were to read it again, I might relate to the main character in “The Dead Zone.” I no longer laugh at “Overboard,” whose myth/related ending resolves abuse too easily. Popular fictions in books, movies, and myth wrap up painful stories without risking a “wrong” ending.

Memoir doesn’t allow the writer that luxury.