Metaverses

This column isn’t an argument for or against any life choice – rather, an exploration of a concept that has been the stuff of science and fiction for a long, long time. That is, what is “real?” Would we know it if we saw it?

Put together, “science” and “fiction” gave us one of my favorite genres of literature: science fiction, or sci-fi.

When I was very young, my route to and from grade school took me by a branch of the Buffalo Public Library, and this charming former mansion was my introduction into many branches of literature – but, at least as I remember it, I read my way all the way through the science fiction section, starting with such greats as Asimov and Clarke, and all the way through Verne and Wells.

Jules Verne, often called “The Father of Science Fiction,” wrote “Journey to the Center of the Earth” in 1864, and while it would be perhaps dismissed by today’s sci-fi fans as primitive in execution, the concept – that there is another world waiting for us deep within the earth – is perhaps not so silly.

At least, not when you consider the metaverse. We’ll get there in a moment. Robert Heinlein, whose novel “Red Planet” was another one of my early discoveries, was also responsible for the famous “Stranger in a Strange Land,” introducing us way back in 1961 to the idea of a human raised outside the sphere of human influence, who has, as a result of his Martian upbringing, the ability to “grok,” or understand something on a sort of molecular level – a connection deeper than something merely emotional or physical. In other words, an experience that was beyond the “normal” human one.

In 1999, the hit movie “The Matrix” was released. Its premise wasn’t entirely new in the sci-fi world. In it, the machines have taken over, and raise crops of humans in pods to exploit their physical selves to produce power to maintain the “lives” of the code-driven machines. This film explored the idea of reality given that all that the human “network” experienced was an endless dream supplied by the machine code to their sleeping minds; everything is perfect, they themselves are ideal. But they don’t know any better.

Way back in the 1800s Mary Shelley speculated in “Frankenstein” about what might happen if a human being were to create another human being – and the experiment went awry. Did this human being have a soul? Was it merely parts sewn together and a beating heart, or something more?

The “metaverse” was a word first used by author Neal Stephenson in his book “Snow Crash,” written in 1992, and exploring the possibilities of “what comes after the internet.”

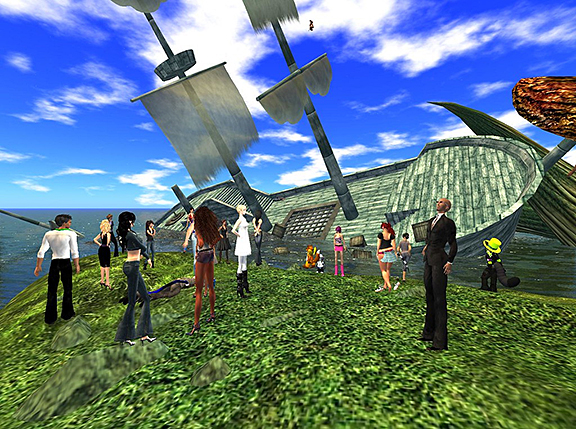

In Stephenson’s story, there is a parallel world, along the lines of what was then being called an MMO (massively multiplayer online game), in which users create an avatar to represent them as they explore. In other words, they are playing God to their own creation of self.

As with most worlds, there are soon social strata arranged in which those with technical know-how and access to superior tools become the nobility, and those who must log in to the “game” from a public access terminal or who lack tech skills are soon shoved down to the lowest rungs of the gaming ladder.

It’s both fascinating and alarming how some 30 years ago, Stephenson could foresee a world which would extend to anyone and everyone (think of online games for kids, where very young children are literally doing just as Stephenson predicted and not just creating avatars but dressing them up with extras in terms of hair, weapons, outfits, abilities like flying or getting extra “lives” – that is, if you have the deluxe package); but might actually extend to the “real” world – in which people of any age can create an

“avatar,” which might mean something as simple as choosing one’s hair color or the shape of one’s nose; to something more at issue and being able to do this at will, and with the cooperation of first our social circles, and now, perhaps, our greater world at large – school, work, and beyond.

Today, we are, in a very real sense, more than the sum of our biological parts. We have, of course, for a long time, assumed that we had a “soul,” which was a layer of non-biological intelligence and purpose, which had merit and value – and presumably an eternity beyond its stay on earth in a body. Not that long ago, after platforms like Facebook presented a public face to our world online, the question arose: what happens when the account’s owner dies ITRW (in the real world)? The account would simply live on. And while that problem has been solved, there are many of these representatives of our living selves that will continue, without some fail-safe like account inactivity for some extended period of time, long after we’ve gone.

Do androids dream of electric sheep? (See Philip K. Dick for the answer)