Publishing, 2024

I’ve been curious about a couple of things to do with book publishing lately: do editors still exist, and what is the state of publishing in this era of e-books and self-publishing?

I began to consider what I knew about the history of book publication, and realized that while my understanding of “modern” printing is that it dates back to Johannes Gutenberg and the first printing press. As it turns out, that is, indeed, the first MODERN printing press – and that “books” go back to the Sumerian, proto-Elamite and Chinese cultures where clay, woodblock, silk printing, and even a movable type system existed and were in relatively wide use. There is a prodigious amount of history throughout Asia and the Eastern world on printing, but for purposes of my question about publishers in the modern West – and because it far exceeds the scope of this article – that will have to wait for another search!

However, to get at my question about modern publications, the history does, indeed go back to Gutenberg and movable type. (To be fair, there is some speculation that even THIS technology might go back to China and the concept of movable type migrating to Europe via Marco Polo and it having been brought back from the Orient along with spices and silks.) His Bible publication (1447) quite literally changed the world. The availability of Bibles, as well as religious tracts, for anyone and everyone to read sparked the Protestant Reformation, and led to the widespread availability of books across Renaissance Europe.

Within a couple of decades of Gutenberg’s Bible becoming widely available, print shops began to open, with “master printers” selecting, editing, and printing various works – including poetry, histories, images and tracts. Between 1500 and 1700, a system became established in which a book would be offered by a printer and readers could “subscribe” – somewhat like a magazine – and print runs, and costs, would be based on the subscription numbers. Later, installments of a book would be offered, which was quite an incentive to get readers to subscribe, as it was the only way to finish a book once started!

The printing press became a very popular technology in the British American colonies – and it has been suggested that it helped spread the revolutionary ideas that created the United States of America.

Some historians credit the first work of fiction to Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, in 11th century Japan (The Tale of the Genji), but I can recall being taught that the first modern English novel was the work of Samuel Richardson with Pamela, Or Virtue Rewarded, written in 1740.

The job of first literary agent, the person who finds the stories, works with the author to make them saleable, and then finds a buyer who will invest in printing it, goes to A.P. Watt, a Scot from Glasgow who began as a bookseller, and who by the end of the 19th century was representing (and selling) such writers as Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, and Arthur Conan Doyle.

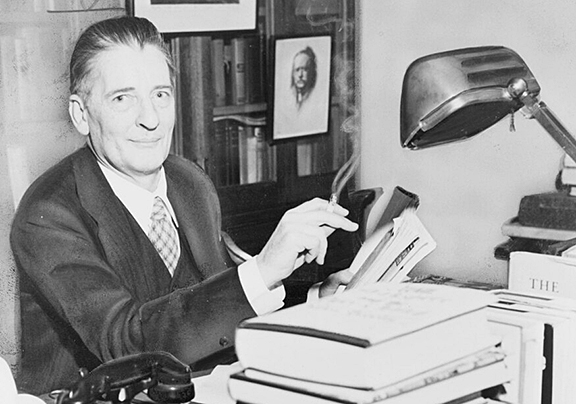

And that brings us to the concept of the modern agent/editor who was quite literally in a partnership with his/her writers – people like Maxwell Perkins, the name my teachers usually invoked as a shining and successful example of one indispensable part of the literary team that made 20th century novels excel.

As Wikipedia sums it up, “Perkins joined the publishing house of Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1910 as an advertising manager, before becoming an editor. At that time, Scribner’s was known for publishing older authors such as John Galsworthy, Henry James, and Edith Wharton. However, Perkins wished to publish younger writers. Unlike most editors, he actively sought out promising new authors; he made his first big find in 1919 when he signed F. Scott Fitzgerald. Initially, no one at Scribner’s except Perkins had liked The Romantic Egotist, the working title of Fitzgerald’s first novel, and it was rejected. Even so, Perkins worked with Fitzgerald to revise the manuscript until it was accepted by the publishing house.

Its publication as This Side of Paradise (1920) marked the arrival of a new literary generation that would always be associated with Perkins. Fitzgerald’s profligacy and alcoholism strained his relationship with Perkins. Nonetheless, Perkins remained Fitzgerald’s friend to the end of Fitzgerald’s short life, in addition to his editorial relationship with the author, particularly evidenced in The Great Gatsby (1925), which benefited substantially from Perkins’ criticism.”

So when was it, I continued to wonder, that this magical relationship among writer, agent/editor, and publisher/printer seemed to have changed?

My suspicions began to arise when I began to note print errors, spelling and grammatical errors in books. Sure, you can expect the odd typo in a quick-to-press daily, but in a book release you would have been shocked to find a word misspelled or a missing period. Not so much anymore. Then I began to catch more subtle issues: why did a chapter go on so long after it was actually concluded? How did an obvious plot failure not get picked up? Was this character necessary?

One possible answer is that the Maxwell Perkins style editor is not what is happening now. A publishing house is as likely to (at least in the case of smaller houses) be a self-publish option. The term “vanity press” is no longer being associated with taking your book to the public directly. Since many publishers aren’t relying on agents to bring them well-written books, perfectly edited and timed for big sales, that whole system has been interrupted. As has been noted so often, when you want to understand how something works, “follow the money.” The old system was: the agent finds a writer he believes will sell, and sell big. He works out a deal with that writer, edits (or hires an editor) the work, and then pitches it to publishers. The publishers soon learn whose “finds” sell the best – and many eventually hired that winning editor/agent and had them scout properties and bring them right to the publishing house. Everyone was in the arrangement to take a piece of the profits, and the writers who got published were usually the ones who were successfully appealing to the reading public.

The newer system is more like this: the writer has an idea, and might do a complete draft. This draft, or a work-in-progress, can be taken to a “coach.” The coach might work with the writer through the process, or read the draft and help the writer create an edited work. The coach, or a hired editor, will attempt to fix the typos, grammar, spelling, and other issues to get a working draft ready for print, and might also work with the writer on revisions that make the story flow better, or target a particular audience more closely. The writer then might approach publishers for a deal, or go direct to print at a fee, or a purchase of a minimum number of books. Book stores are often free to pick up self-published authors, or the writer might sell his or her book directly, through online outlets or a website. Where once the publisher would undertake the work of promoting the book, much of this is left to the writer in the modern method.

But in this system, depending on the level of inspection, and possibly the size of the fee for the editing, there may or may not be as careful a look at a given book – and a particular agent/coach like a Maxwell Perkins might not become well known as the “magic maker” who can bring out the absolute best in a specific writer, or type of writer.

And, as might be expected, there are now A.I. book “editors,” that can be assigned the duty of picking up basic spelling and grammatical errors.

Of course, though much of the world of books, book publishing and sales is changing, it is still the case that a truly excellent effort, new take on a classic and beloved essential story, or vibrantly imagined main character will always grab readers attention, and be widely read and much-discussed (and often optioned for film!). It just may take a few more attempts to find, in this wealth of options, that gem you can’t put down.